Candy Crush, Clash of Clans, Flappy Bird – if you’re a fan of gaming on mobile devices, you’ve likely already heard (and are probably already playing) one of these wildly popular games.

For years, cybercriminals have been picking apart and repackaging these types of widely downloaded applications with malicious code, re-uploading the Android APKs to the official Google Play and third-party application stores, in the hopes of tricking users into downloading Malware. The name recognition of these applications can lull users into a false sense of security, thinking they are downloading the official applications, when in-fact they have been silently compromised.

The challenge for attackers with repackaging famous applications is the increased scrutiny they receive, with Google Play often identifying these malicious copies and removing them before they can do much harm. Palo Alto Networks researcher Zhi Xu, an expert on mobile malware, recently discovered a new trend in the distribution of malicious applications, which as of this writing are live in the official Google Play store: repackaging popular open source applications from GitHub with malicious code.

The malicious samples Zhi analyzed were pulled off live enterprise networks over the past few weeks by Palo Alto Networks WildFire, which automatically gathers suspicious files from more than 3,000 organizations to discover unknown malware, zero-day exploits and Advanced Persistent Threats (APTs), and generates protections for all newly discovered threats.

Details on the malicious Android APK:

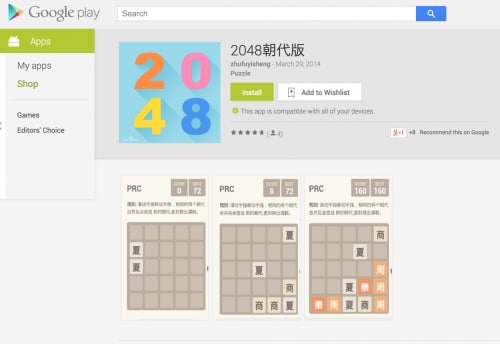

- Attackers repackaged a popular open-source Android application posted to GitHub: http://oprilzeng.github.io/2048/full/ which contains a host of Adware, generating revenue for the malicious actor each time the app is used

- The malicious repackaged App is posted under the APK name, “com.zhufu.chao2048” and currently available for download, with a 5-star rating

Details on the Adware:

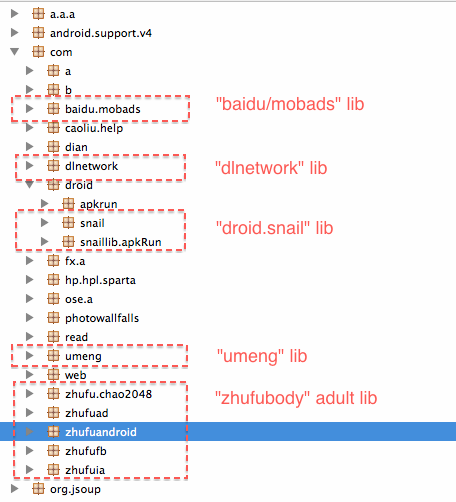

The “com.zhufu.chao2048” APK file added the following contents to the original app on GitHub, each of which is a content library that displays Ads and generates revenues for the malicious actor:

- Distribution of advertisements (baidu/mobads lib)

- Distribution of adult advertisements (zhufubody lib)

- Collects private user data for to aid in the distribution of advertisements (dlnetwork and com.droid.snail lib)

- Analytics to better target advertisements (umeng lib)

Further analysis by Palo Alto Networks revealed two additional repackaged versions of the same open-source GitHub application:

- “com.app93.chaodai2048” app: added “google.ads” and “umeng” ad libraries

- “in.zerob13.game.two048” app: added “youmi” ad library that collects user’s private information including current location and device id.

As of April 15, these applications have been downloaded up to 5,500 times by users on the official Google Play store. It is important to note that this malicious application falls into the “Adware” category, and isn’t stealing sensitive information from compromised users.

While these examples did not contain dangerous malware, attackers could just as easily repackage popular open-source applications with more malicious intent in mind. Since they are not stealing known apps from the Google Play store – an activity that would trigger alarms more easily -- this technique could allow them to fly under the radar and continue to infect users over an extended period of time.

Our discovery showcases that there is typically no easy way for the average user to know whether an open source app and the package found in an app store are indeed one and the same. The typical user simply sees the app and installs it, not knowing that there is no process to correlate whether it was built by the official package maintainers or not.

These apps highlight the need to place greater scrutiny upon the apps used in enterprise mobile devices. This includes the examination of app behaviors to understand whether or not there are latent risky or malicious functions in them. Enterprise security practitioners need not only the ability to identify malware, but also the means to spot devices that have these apps in installed and establish corresponding policies.

In addition, many of these apps use the network to download other pieces of code and to communicate with the attacker, and organizations must set policies that can break the threat lifecycle by dismantling the malware’s ability to establish command & control channels.

For more information about how to secure mobile devices visit: